And finally, this 1992-inspired league-style World Cup has come to an end. From 16 teams in 2007 and 14 in 2011 and 2015, this edition featured a measly ten sides. As the dust settles, what is the verdict on this everyone-plays-everyone format?

There are two distinct facets of the debate around this schedule. The first discusses the merits of the 10-team league format itself. The second argues against the very idea of a World Cup limited to just ten teams. Often, the defence of a larger, more inclusive tournament gets conflated with a criticism of the league stage itself.

Concerned cricket fans desiring more teams on the biggest stage hurry to highlight the demerits of the league. It’s important to disentangle the two arguments.

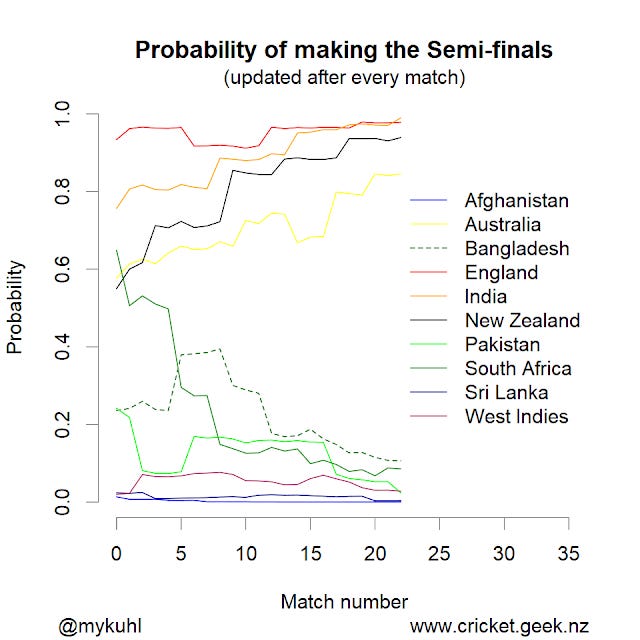

45 league games in one single round, and just 3 knockouts. Does this provide exciting cricket? The answer is heavily dependent on the quality and relative strength of the competing teams. Midway through the league stage, the final 4 were almost decided:

It was a series of stumbles by favourites England, and an inspired resurgence by Pakistan that made the fight for the 4th spot interesting.

A big league is interesting only if a large chunk of teams are similarly placed, are equally strong or equally flawed. In the 2019 IPL, 4 teams scrambling for the final two positions made the latter stage interesting. A boring World Cup was given similar life in the middle stages. The point remains that this format could very easily have produced a World Cup full of dead rubbers. That the league heated up at the end was an artefact of the surfacing flaws of the top teams.

Another point often used in favour of this format is that it “rewards the best teams”. While that is true, there are multiple contradictions that need addressing.

First of all, if the objective is sieving out the best team to crown them world champions, why have any knockout element at all? Why not just make the league topper the winners, or have a playoff system, or a series of knockouts? In this edition, the teams ranked 3 and 4 made it to the final. If the idea is to really reward the most consistent team, why should one bad day knock the top 2 out? So, this argument of “best team” is deflated by the tacking of knockouts onto the league.

Now, if your answer is that knockouts are important to build excitement and give context, with the best teams playing each other in high pressure games, you’ve reached my next point. A World Cup needs context and excitement to each game, which is imposed externally through a structure of rounds. This structure of rounds should ideally ensure that almost every game is important (high pressure) and the best teams progress through and play each other.

A bloated league stage which is the only round doesn’t do justice to a World Cup. The early games are too far away from the next round to really have excitement, and unless the mid table teams do well as some other teams falter, the final games become dead rubbers. In any case, relevance and pressure are infused into games through the presence of stages and immediate pathways for progression to the next stage. In this format, those discussions start only on the final third of the phase.

Russell Degnan has written on the potential excitement of formats for Emerging Cricket previously.

In any case, there already is a system to reward the best, most consistent side in a league-esque form: the ICC ODI rankings. This is now going to be formalised as the ODI Championship. The World Cup needs to be something else.

With the format dissected, we must now address the elephant in the room. Should something called the World Cup have just ten teams?

The first argument touted in support is that the ten “best” teams play, producing “exciting” cricket and fewer one sided matches. As this excellent analysis shows, it turns out the while Full Member-Associate matchups are indeed more one-sided, World Cup matches in general have been won by heavy margins.

Nick Skinner with an excellent essay for Emerging Cricket destroying the argument against the inclusion of Associate / weaker teams.

To add to this, the label of the ten “best” teams is arbitrary, since any one of the lower ranked teams can beat any other on a given day. Scotland has bested Sri Lanka and England recently, and Ireland could beat Afghanistan in fast conditions. There is no fair way to determine which teams make the cut. There is also no guarantee that higher ranked teams put up a better fight all the time. South Africa and Pakistan got comprehensively beaten by India, while Afghanistan ran both India and Pakistan close.

As the above linked essay concludes, considering data since the 2003 World Cup, Full Member-Associate Member games have a 36% chance of upset if the ranking difference is within 3 places. The same figure for Full Member games is 41%: not a huge difference.

A World Cup is the biggest showcase in cricket. It’s a stage for everyone to perform against all others, and it holds within it the capacity to make heroes and change the whole game in a country. Ireland’s win over Pakistan in 2007 set them off on the road to Test status, for instance. Not everyone competes to win the trophy, some just do it to show their mettle on the biggest stage. The benefit to their cricket in terms of experience, and to their fans at home as inspiration, is unquantifiable and magical.

The pros and cons of the ten team round robin, in isolation, can be debated at length, but they should be irrelevant. Little moments of magic grow this glorious game, and a World Cup must promote this by including a fair number of teams. There’s no better example than a motley crew of highly improbable winners on the Lord’s balcony 36 years ago. No one gave them a chance then, and now their country could argue convincingly that theirs is the actual “home” of cricket.

Originally published on r/cricket | Photo: ICC/Getty